Airborne wind energy is a generic name that describe various technologies that have different levels of development.

They have in common the idea of using unmanned vehicles such as planes, kites, balloons or similar solutions to produce energy from the wind. These vehicles are generally “tethered” (that is, connected to the ground).

Their main promise is to give you “more energy with less material” – because they have a lower initial cost and they consume less material. They also have several other potential advantages. For instance, they could be deployed relatively quickly in areas where there is urgent need for electricity (for instance after a disaster).

Researches on this technology started in the seventies but accelerated greatly in the last 10 to 20 years, with dozen of company developing different ideas and registering hundreds of patents.

There is still no consensus on which is the best technical solution. Therefore there are significant differences between the technologies currently being developed.

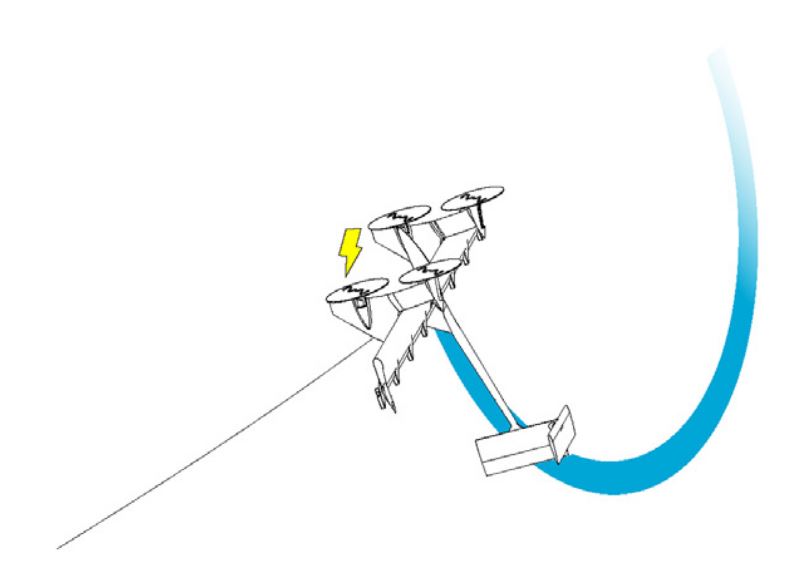

A first distinction can be made between systems that produce energy in air inside the flying unit (“on-board generation”) and those that have a generator inside a ground station.

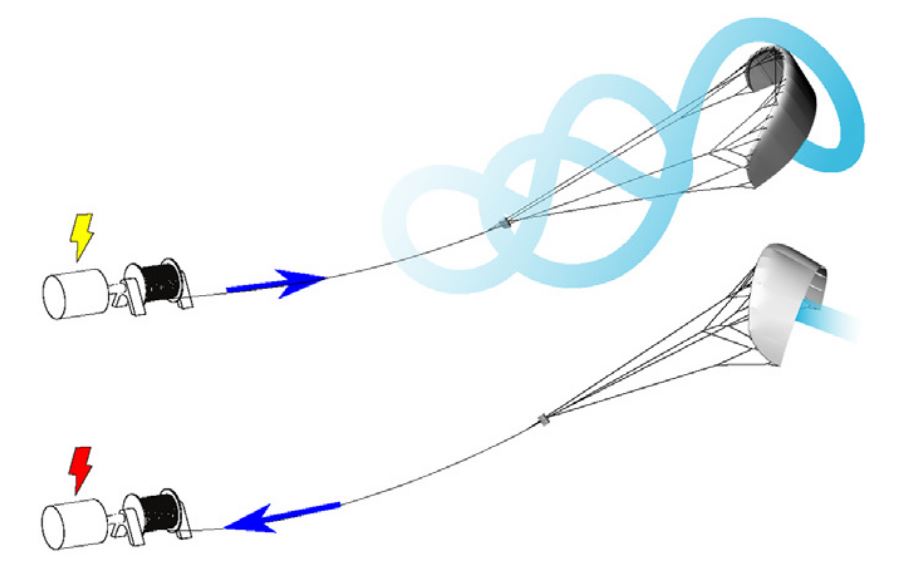

This ground station can be fixed or move (for instance on a loop track or an horizontal track). There are different possibility to produce energy in the ground station: for instance, the tether can unroll a cable around a drum, and the rotation of the drum can be used to produce electric energy.

This mechanism remember somehow a yo-yo – you can see how it looks like in the following picture.

The system work with a two-phase cycle: a “generation phase” where energy is produced and a “recovery phase” where the rope is rolled up again changing the flight configuration (and possibly, consuming some energy using an electrical motor to rewind the rope).

Several others possible categorizations are possible, for instance depending on the wing type used by the system (rigid wings vs. flexible wings), their weight (lighter vs. heavier than air) or considering the take-off mechanism used (vertical vs. horizontal).

Rigid wings have a better aerodynamic efficiency. Additionally, they usually also have a longer durability. Soft wings, on the other hand, are lighter and more effective with ground generating systems (decreasing the flying mass increase the tension on the cable).

How high will they fly?

The objective is to fly higher that the current wind turbines, to find stronger and more consistent winds (as a general rule the turbulence of the wind decrease with height).

Although it would be nice to extract energy from jet streams at 8000 meters (the strong winds blowing in the upper atmosphere that can make your airplane fly faster) there is evidence that at such altitute the cable that connect the vehicle with the ground would dissipate a significant amount of energy due to aerodynamic drag.

This could imply operating the system at a much lower altitude – probably in the 200m to 2000m range, with an optimum that will be location specific.

Investigations are also focusing on how to solve the take-off problem: as the vehicles are not propelled they will have a very low speed during take-off, and this imply less controllability of the vehicle.

The inverse problem (landing) is equally relevant: it should be possible to stop the system quickly in case of an emergency, as it is possible with a wind turbine.

To solve these problems and to maximize energy production the companies working in this niche are using algorithms to control the flight.

Another problem that the engineers are trying to solve is how to find a balance between low cost and reliability: these machines have moving parts and are supposed to have a long useful life (at least compared to the current lifespan of a wind turbine, which range from 20 to 30 years). The cost of maintenance should not offset the low initial investment cost.

Making a prediction on “social acceptancy” is much more complex (and not only because I am biased and I believe that wind turbines are beautiful).

There is some possibility that people will think that kites and balloons are more attractive than standard wind turbine. Can you imagine a wind farm made from giant helium-filled balloons? I’m sure my children would love it.

However, the path towards the implementation of these solutions still seems long and complex.

A few months ago (February 2020) Google closed Makani, one of the companies more advanced in the research for airborne turbines.

Makani was a start-up founded in 2006 and acquired by Google X in 2013.

Makani made several working prototypes and was considered in pole position to find a working solution, also because their parent company has very deep pocket. Therefore their closure was a shock for the industry.

We will probably still need towers and foundations – at least for a while.

Leave a Reply