Have you ever wondered why sometimes the wind turbines (and other similar tall structure) sometime vibrate?

Under some conditions the wind blowing on the tower create vortices.

These vortices appears regularly on both sides of the tower, creating low pressure zones first on one side and then in the other.

For these reason the tower will start moving perpendicularly to the wind, first toward one side and after toward the opposite.

The tower has a very low structural damping – when the oscillation start its reduction is very slow because the steel tower has a limited capacity to absorb the kinetic energy.

It also has a very low natural frequency (the frequency at which the tower will tend to vibrate when subjected to external forces).

The vortices created by the wind will appear at a frequency that depends on the speed of the wind and the diameter of the tower.

The formula to calculate this frequency is very simple:

f = St · U / D

where

f is the vortex shedding frequency

St is a value called Strouhal number (in our case it is around 0,2)

U is the wind speed

D is the diameter of the tower

At a certain wind speed the vortices will appear and shed at a frequency equal to the natural frequency and the tower will resonate. The wind speed that start the resonance is called the critical speed.

If the wind blow at the critical speed for enough time the amplitude of the vibration will increase and you will see the tower oscillating.

This is a simplistic summary of a very complex phenomenon. It is however a limiting factor for the use of higher steel tower. In additional to the risk of catastrophic failure the wind induce vibrations will also generate additional fatigue loads, shortening the life of the tower.

It is also interesting to observe that a structure has more than a natural frequency.

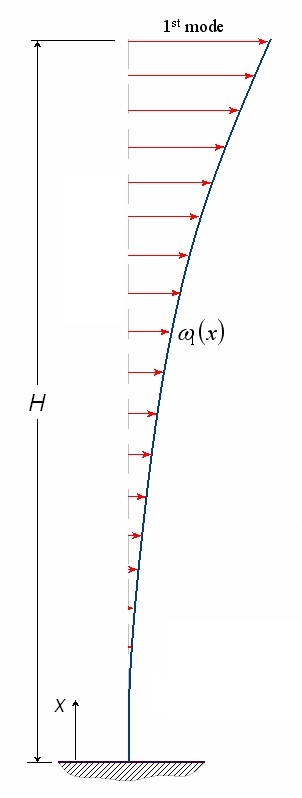

Vibrations in the lowest natural frequency (first mode) will have this shape:

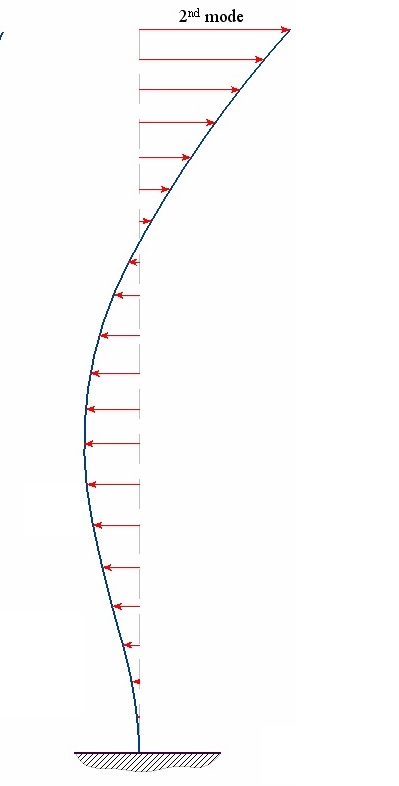

However, sometime a turbine can vibrate in what is called “the second mode” the second lowest natural frequency):

Following this link you can see a real world example of how is a tower vibrating in the second mode.

What can we do to avoid these dangerous vibrations?

Some solutions are structural – basically aimed at increasing the damping of the tower or changing the way the mass is distributed.

It is not easy to change the mass distribution in a wind turbine tower (basically its an inverted pendulum).

Nevertheless it is possible (and it is becoming increasingly common) to install dampers in the wind turbines, either only temporarily during the installation or as a permanent feature.

Other solutions are aerodynamic – the idea is to change the shape of the tower adding elements that disrupt (or “spoil”) the vortices. Conceptually they are similar to the spoilers used in cars or planes, in the sense that they are intended to mitigate an unwanted aerodynamic effect.

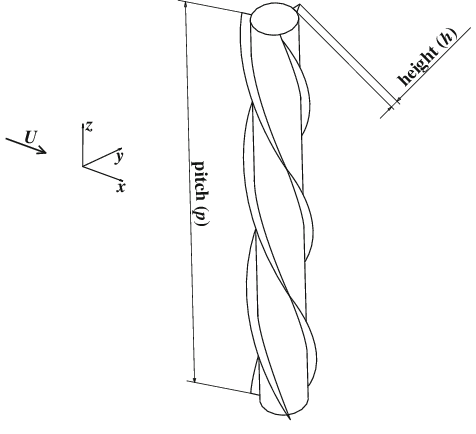

An example are helical strakes, sometimes called “coils” “ropes”. This is a concept developed by Christopher Scruton and other scientist such as William Weaver in the fifties and sixities and used often in chimney and similar structures.

However sometimes they do not work as you can see in the video below.

In general, the effectiveness of this solution is driven by two parameters:

- Diameter of the strake (usually defined as a ratio of the diameter of the tower)

- Pitch (the distance along the cylinder axis that is needed to complete one full turn of the strake)

From experimental tests in wind tunnels it has been found that the optimum height of the strake is approximately 10% of the diameter of the tower (that is, around 40 cm for a standard steel tower with a diameter of around 4 meters).

For the pitch the results of the test shown an optimum value in the region between 5 and 15 diameters (that is, one full turn of the rope should be done between 20 and 60 meters).

Obviously the smaller the pitch, the more the strake is parallel to the tower.

There are however other secondary factors that influence the efficiency of this solution, such as the area of the cylinder covered by protrusions (usually called “strake coverage”) and the pattern of the ropes (usually three or four independent ropes are used to create the helix).

One of the biggest problems of the strakes is that they greatly increase the drag coefficient (the resistance opposed by the wind turbine tower to the flow of the wind).

The implication is that the loads at the bottom of the tower will increase as well, so that a bigger foundation could be needed.

For this reason strakes are normally used as a temporary solution only during the installation – above all in the most critical part of the procedure, when the tower is installed but there is still no nacelle on top.

Removable strakes are wrapped around the tower, either before the lift while the tower segment is on the ground or after installation.

Bonus: poetry & technology (from a LinkedIn post of Hervé Grillot)

Leave a Reply